Google may be the first name associated with driverless cars, but they’re not the only ones interested in the technology. More importantly, it seems people have wildly different opinions on exactly how the story will play out. How much data will these cars produce? What kind of legal quandaries will we face? While the details are hazy, there is no doubt these machines will not only be available in the near future, they will soak up data like a sponge, and put that information to use both inside the car and out.

Where does all this data come from?

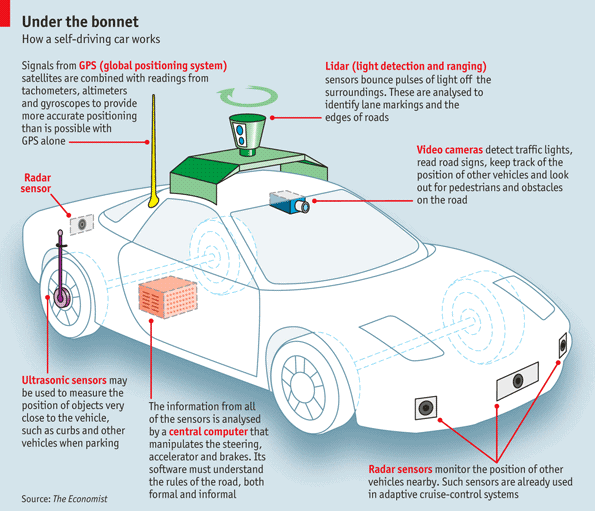

When a passenger loves their car very much, they go on trips. Of course, for a driverless car, it can be a little hard to see the road. This is why they are loaded with sensors. They may be equipped with Laser Illuminating Detection and Ranging, like Google cars, which are used to build a 3D map of the surroundings. It can see lines on the road to know where the lane is, or notice that a light has turned red. Now the car can see, but what about those other cars zooming about? How can a driverless car avoid a fender bender? Once the car is equipped with radar units the car can see just how fast the surrounding objects are moving.

There are three main hardwares in the driverless car model: sensors, processors, and actuators. Images and information gleaned from sensors travel through the processor, which effectively tells the car what to do via actuators—tools that allow a computer to control physical components like brakes, or steering wheels.

Certain kinds of data can also come from other cars. Your little car is not alone on this journey from toddler-brained-automobile to futuristic sci-fi car. Data from other cars is also used to better map environments. If cars were to process the image of a new stop sign put in place, that data would eventually become part of the overall mapping system. Thanks to cloud access, the car is always connected and, ideally, up-to-date.

Certain kinds of data can also come from other cars. Your little car is not alone on this journey from toddler-brained-automobile to futuristic sci-fi car. Data from other cars is also used to better map environments. If cars were to process the image of a new stop sign put in place, that data would eventually become part of the overall mapping system. Thanks to cloud access, the car is always connected and, ideally, up-to-date.

These cars aren’t just lumps of smart technology; they’re the result of learning algorithms, and catalogued information based on previous experience. It’s the incredible software in place that models responses and behaviors in real time. The more the car, or computer, drives, the more it knows. This doesn’t mean you have to educate your car. Rather, the problem is in the very specific split-second decisions that drivers make every day. Scientists can’t possibly program a car to recognize every little objects and how to act in every situation. A car may not inherently know the difference between a glass bottle or a newspaper, but by absorbing more data through driving and real experience, it may learn. It may learn that items in the road will cause other drivers to swerve, or how to anticipate when a driver will change lanes.

By turning driver experiences into programmable information, scientists can also make driverless cars much more practical. The ability to relay all kinds of data at once doesn’t necessarily equal the perfect car. There don’t need to be flashing lights every time another car brakes; it shouldn’t brake every time a bird is in the street. The results would be overwhelming. There is a multitude of background noise that drivers tune out to focus on what is vital. That’s why data science is necessary to determine what is and isn’t important. These cars use predictive and prescriptive models to deal with the influx of sensory information in a practical way.

How do we manage that data?

While scientists continue to argue over the exact number, some strategists argue that driverless cars could create up to 1GB of data per second. Given the number of sensors, and the fact they must constantly transmit information, it isn’t hard to believe such a high number. Theoretically that would equal petabytes of data a year, just from one measly car. The counterargument often concerns what actually happens to this data. Obviously, not all data from every car will be considered important. Rather, only important information would actually be stored. As most data is simply used for active driving, not for detailed analysis, those petabytes of data wouldn’t end up on the cloud. Much like unnecessary food photos, no one wants to see the 5,155th photo from your rear bumper—and no one likely will.

There are so many concerns about how the data from driverless cars will be put to use, but the fact is that, in order to get where they are now, designers and manufacturers have already absorbed exorbitant amounts of data. In order for the Google Self-Driving Car to maneuver the 2,000 miles they operate on is because the area is entirely pre-mapped. Every drive along these streets creates more data, making it safer and more reliable. What happens if you drive outside of their small pre-mapped area? Frankly, your car might not know what to do. There is no taking your unmanned car for a spin through uncharted territory. It will take time and the sharing of data to create bigger and better maps. No one company will be charting the entire globe, alone. The more companies experiment and create, the faster they can absorb and analyze the mountains of data standing between the cars of today and the future. Moreover, many speculate that the development of better techniques will make a lot of data more accessible to those in other fields. While not all car, tech or logistic companies can afford to invest in driverless cars, they too may benefit in the long run.

Apart from problems of public acceptance and legal complications, autonomous cars also include a risk of security and personal data-related problems never before experienced on the road. While the data might be perfect, such cars are hackable—as has been recently proven when two hackers took out a Jeep on a highway (purely for science reasons, thankfully). If you can keep your car safe from hackers, you may still have to worry about your personal data. The absolute terror that advertisers will track consumers and direct stream commercials to the dashboard is a real fear that will be hard to sooth. There is money in data, and stopping that kind of innovation might be an uphill battle.

Nonetheless, the mixture of complexity and common sense that is driving automated cars is breathtaking. The magic isn’t just in images of driverless, hovering cars (obviously, all futuristic cars can hover), but the ways that scientists are teaching computers to learn. No, they might never be capable of split-second decisions quite like a human, but with the right data, teachers and algorithms, robots can mimic the human mind very well.

Like the article? Subscribe to our weekly Newsletter.

image credit: The Economist