The Dutch police have utilized a deepfakes video to appeal for information on the 2003 murder of a young boy. According to authorities in Rotterdam, it is a “world-first” inquiry using artificially altered video.

What are deepfakes?

A deepfake is a form of artificial intelligence that may be used to generate realistic images, and audio and video hoaxes. The generator and the discriminator are two AI algorithms that are used to create a fake video. The generator, which creates phony multimedia content, asks the discriminator to determine whether the material is genuine or artificial. Deepfakes are made using generative neural network technologies such as autoencoders and generative adversarial networks (GANs) to adjust or create visual and audio content.

Neural networks were previously excellent at classifying existing material (for example, understanding speech or recognizing faces) but not at generating new material. GANs gave neural networks the capacity to not just detect things, but also to create.

The first stage in building a GAN is to choose the intended output and design a training set for the generator. The discriminator may then be fed video clips after the generator has generated an acceptable quantity of output.

As the generator improves at mimicking video, the discriminator gets better at detecting them. In contrast, as the discriminator improves at detecting false video, the generator improves. For instance, there i a new neural network that is able to read tree heights using satellite images.

How Dutch police have utilized deepfakes?

Deepfakes are already used for malevolent ends such as the illicit manufacture of sexual material without permission, fraud, and the creation of deceptive content designed to influence public opinion and democratic processes.

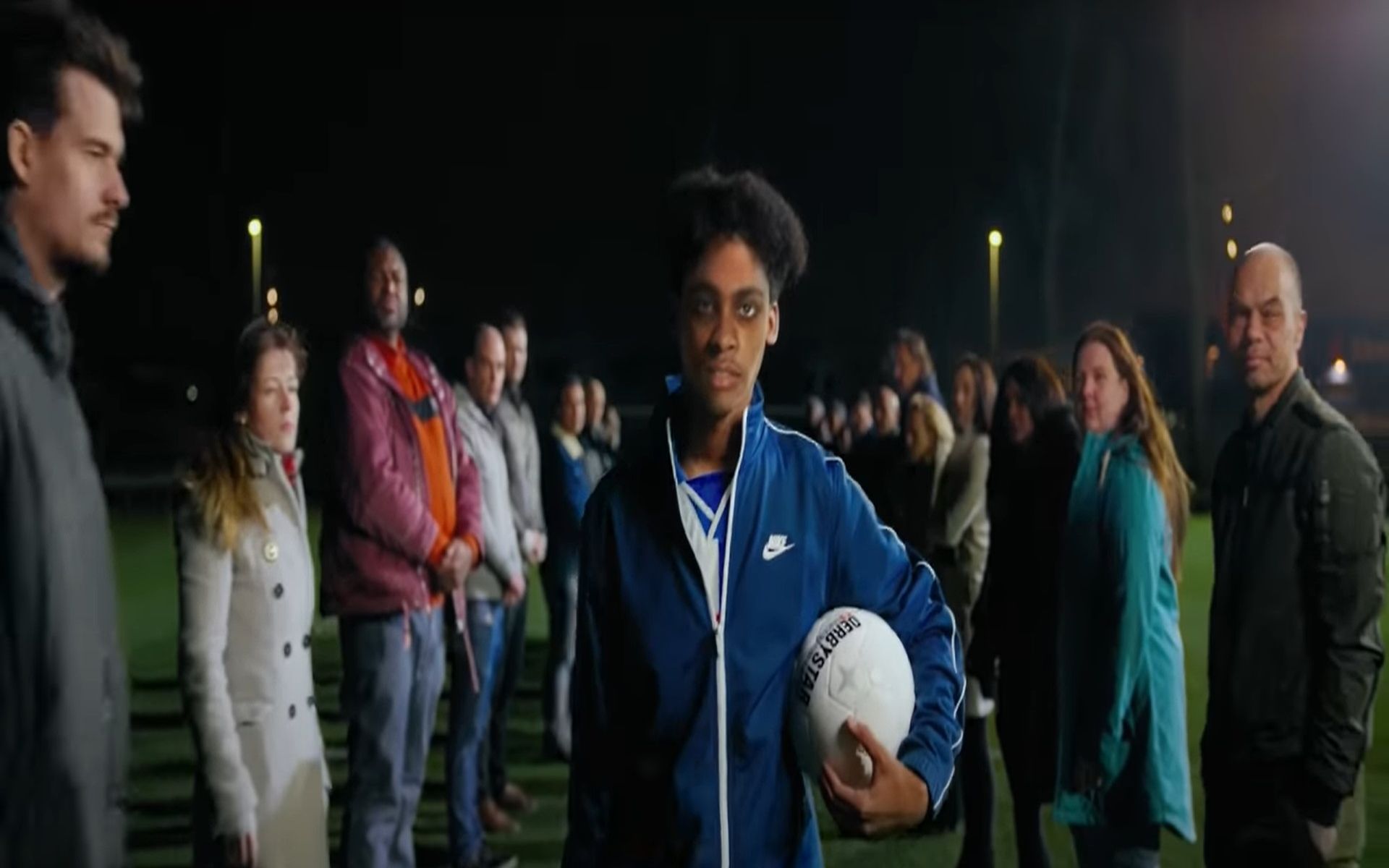

However, in Rotterdam, officials have proved that the technology can be used for good. Dutch police developed a deepfake video of 13-year-old Sedar Soares in an attempt to solve his murder after he was murdered in 2003 as a young footballer who was throwing snowballs with his friends at a subway station’s parking lot.

Soares is seen picking up a football in front of the camera and going through a guard of honor on the field that includes his family, friends, and former teachers in this video.

“Somebody must know who murdered my darling brother. That’s why he has been brought back to life for this film,” says someone in the video before Soares pitches his ball.

“Do you know more? Then speak,” his relatives and friends urge. The video then provides the police with contact information. It is hoped that the moving film and a reminder of Soares’ appearance at the time will encourage people to recall him, leading to his case being solved.

Detective Daan Annegarn, a member of the National Investigation Communications Team, stated:

“We know better and better how cold cases can be solved. Science shows that it works to hit witnesses and the perpetrator in the heart—with a personal call to share information. What better way to do that than to let Sedar and his family do the talking? We had to cross a threshold. It is not nothing to ask relatives: ‘Can I bring your loved one to life in a deepfake video? We are convinced that it contributes to the detection, but have not done it before.‘ The family has to fully support it.”

So far, it appears to have worked. The Dutch police claim to have already received several tips, but they must determine whether they are genuine. In the meantime, anyone who has any information is urged to share it with the authorities.

“The deployment of deepfake is not just a lucky shot. We are convinced that it can touch hearts in the criminal environment—that witnesses and perhaps the perpetrator can come forward,” Annegarn explained.

Authorities are having difficulties when it comes to detecting deepfakes, a new method using self-blended images is developed, though.