This article originally appeared on Hackernoon and is reproduced with permission.

Hyper-casual games have captured the mobile games industry’s interest ever since the incredible meteoric rise (and fall) of Flappy Bird in 2014.

In 2018, the total mobile games market stood at $50 billion, of which $10 billion came from in-game advertising and the rest from in-app purchases. In that same year, AppAnnie reported that hyper-casual games made up 53.4% of the top 30 game installs in the US and over 27% in Japan and Korea, respectively.

Fast forward to 2020, and hyper-casual games are now the most downloaded genre in mobile gaming worldwide, accounting for 31% of all installs, according to data from SensorTower.

The genre doesn’t make as much revenue as others (with RPG games taking the lion’s share). Still, various analysts estimate it is worth $3bn, and with fast development cycles, it is a desirable genre and profitable for developers and publishers alike.

But competition is high, and the global pandemic has caused that to increase. More people are playing throwaway games to pass the time, and more developers are creating hyper-casual titles.

I spoke with Ivan Fedyanin, CEO and co-founder at Ducky – a hyper-casual game publisher with over 40 million downloads – about the latest trends and how hyper-casual developers and publishers can scale in the face of growing competition.

Hyper-casual trends

“We believe it is crucial not to chase ostensible trends,” Fedyanin said. “Occasionally, we notice interesting tendencies in the genre, but they cover only a small proportion of the industry players to be classified as a trend. For example, nearly every quarter, the hyper-casual community starts discussing the shift of games towards a more complex hyper-hybrid genre. Hyper-hybrid implies a more demanding game development process, more elaborate gameplay, and advanced in-app monetization.”

Data and analysis from the likes of SensorTower, AppAnnie, and others suggest every time the industry tries to evolve away from more complex projects, it doesn’t succeed as well as it should.

“Indeed, such projects exist and sometimes show explosive growth,” Fedyanin said. “However, there are significantly more projects with simpler gameplay, generating >95% revenue from ads.”

“In general, trends in the industry include a general change in the quality and cost of games development,” Fedyanin said. “Developers focus much more on improving the graphics and quality of games. They now replace stock graphics and stickmen with proprietary game characters and in-house graphic design.”

And that has an impact, of course, on costs. In an industry where most of the revenue comes from ads, and with mobile ad revenues facing a squeeze, a focus on expenses is essential.

“It becomes even more important to test projects quickly at the earliest stages so that potentially unsuccessful projects can be shut down in advance before a lot of resources are wasted,” Fedyanin said. “Ducky is now able to do the first product tests only after two days of project development and pass on 3 out of 4 projects at this stage. It allows us to help developers focus on products with a higher potential.”

So how does Ducky cooperate with game developers?

“Although we never oblige developers to work exclusively with us, we expect close and trust-based cooperation at all stages,” Fedyanin said. “During the idea generation phase, we monitor the metrics of all games published and share all information with the developer. After the tests, we don’t just send the result along with simple instructions to either keep working on a project or shut down the development. Instead, we analyze as much information as possible to provide detailed feedback.”

Testing, then, is a fundamental part of hyper-casual games if you want to have a chance at scaling and making a profit.

“Our main goal is to help a developer learn how to create a so-called ‘hit,'” Fedyanin said. “We call a game a hit if it reaches more than 10 million installs in the first three months. On average, a developer needs to start 40 projects (and kill 39 of them) before one of them becomes a hit. And this is possible only if the developer learns from his own mistakes, pays attention to the analytics, and conducts frequent A/B tests of new features and content. Our only role in this process is to advise the developer what needs to be done and help set up new procedures.”

Of course, working out which of those 40 projects is likely to be the winner is only part of the puzzle.

“We help a lot to head in the right direction with monetization,” Fedyanin said. “Our expertise here is huge. At the monetization stage, we provide the developer with detailed instructions of what needs to be done. We constantly test new approaches, and when we see that the effort leads to good results, we use those tactics in all our games produced in the future.”

Fedyanin thinks that this kind of advice and collaboration is essential.

“Other publishers often do all the product analytics on their own and just give developers a ready-made set of instructions,” Fedyanin said. “In this case, developers just follow someone else’s advice instead of learning and gaining experience. Usually, it has a negative long-term effect on developers’ quality of work. We show and explain to developers what we are analyzing and how it affects further decisions and results. We teach them how to set up data-driven decision-making and let them do it themselves.”

So what are the main differences between developing and publishing hyper-casual titles versus traditional mobile games?

“The main difference between hyper-casual and traditional mobile game development is the speed of production and the need for testing much more frequently and faster,” Fedyanin said. “Our goal is to iterate hypotheses as quickly as possible and get rid of potentially unsuccessful projects at the earliest possible stage. It allows us to spare resources instead of trying to bring all pre-hit projects from zero to the final step.

That means being brutally honest and making data-based decisions without holding on to projects for ego or personal reasons.

Testing, testing…

“We cut a number of projects out of development after each test stage: CTR test, CPI/R1 test, and monetization test,” Fedyanin said. “During the CTR test, we show the audience a gameplay video when there is no finished game in place yet. It usually takes up to three days to make such a video test the idea. Then we run the ads and monitor whether users will click on them.”

“If we reach a threshold CTR value, the developer needs to keep working on the project,” Fedyanin said. “If not, the idea of a game has to be dismissed because its CPI will be high in the future.”

“During the CPI/R1 test phase, the developer makes a small demo version of the future game, which usually takes 5-7 days to develop,” Fedyanin said. “This version contains only a pure core loop, i.e., the volume of content needed to play for five minutes without any meta-features.”

“During this test, we check the installation cost and user retention,” Fedyanin said. “The secret sauce here is that if the game is interesting, then users will stay in the game even if they stay at the same level forever. We occasionally see that if the game is interesting, even with three-minute gameplay, first-day retention can be 45% and above.”

And, you guessed it, if the game fails here, it gets cut.

“If the second stage was successful, then it’s time to pay attention to CPI and LTV ratio at the monetization stage, Fedyanin said. “This process is longer and takes up to two weeks. In addition to monetization itself, together with developers, we add additional features and content to the game.”

It’s a numbers game

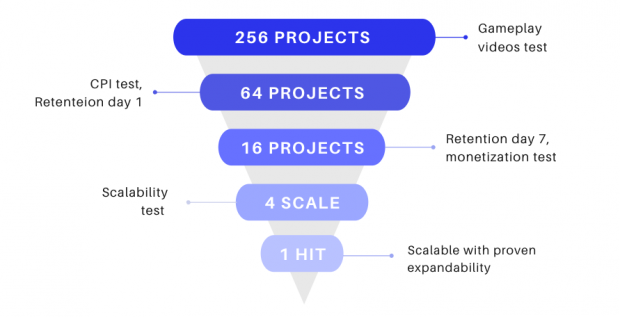

“The path to a hit is paved by a large number of rejected ideas,” Fedyanin said. “After we test 256 gameplay videos, only 64 pass the test. After developers test CPI for 64 prototypes, only 16 meet the requirements. After we check unit economics, only 4 show sufficient metrics. One out of four games has the chances to prove it is scalable enough to become a hit.”

So what has Ducky learned from those games that fail to make the grade?

“Each time, we try to understand why exactly the idea didn’t turn out to be successful, it comes down to several factors,” Fedyanin said. “Sometimes the retention is insufficient, sometimes the CPI rises too fast, and sometimes the monetization is not right for the project. We add this information to the experience log and move on. That said, as someone who has made and published many mid-core and hardcore projects, including American Dad: Apocalypse Soon!, I absolutely believe that this test-driven approach can work in traditional game development as well.”

Other than data-driven decision-making, another critical element of success in hyper-casual games is cost management – the most significant number on the profit and loss sheet is most often the sum of the salaries column.

There are many different approaches to staffing in the mobile game industry. King and Supercell, for example, have shared similar revenue numbers, but King achieves its $2bn revenue per year with over 2,000 employees, whereas Supercell does roughly the same with just over 300.

“We are the proponents of small teams, both in development and publishing,” Fedyanin said. “Hypercasual is all about the speed of iterations, of interaction with the developer, of tests, and of scaling speed. It all gets challenging when there is a complex hierarchy in a company. For that reason, I don’t think we will ever grow beyond 30 people in a publishing team.”

And how many people are in the Ducky team at this time?

“Now the whole Ducky team is 12 people,” Fedyanin said. “With these resources given, we already test more than 200 projects a month and have almost reached the speed of 1 hit per month. We believe that the secret sauce is not in the number of employees, but in the talents themselves. To accumulate the necessary expertise and skills in our team, we don’t need to hire classic executives. Managerial members of our team must be able to do the same things as those his or her subordinates do.”

As far as company culture is concerned, Fedyanin has his views on that too.

“We also do not hire junior specialists for monotonous tasks because they usually cause significant time losses,” Fedyanin said. “Instead, we try to recruit seniors, who can think creatively and come up with easier and faster ways of doing what is required. The skills of any new team member should be above average. Also, we try to set up clear processes in place and automate mundane everyday tasks to avoid operational inefficiencies.”

So what’s next for Ducky?

“Dream big,” Fedyanin said. “Both Alisher Yakubov (my partner and co-founder of the company) and I worked for a major gaming company before Ducky. We realized that with the heaviness of a large corporation, we would not be able to build something really new and market-changing. Not to mention that it would be impossible to do it fast enough.”

“We definitely won’t stop at the status of a tiny hyper-casual games publisher for a small number of developers,” Fedyanin said. “This year, we want to change the market by assisting a lot of developers on their way to a hit. Our goal for the year of 2021 is to reach a rate of 1 new hit per month and grow tenfold to $10 million a month in revenues.”