In 1998, Google’s search journey began at Stanford University with Backrub, a project running on a 40-gigabyte server encased in Duplo blocks. Nearly three decades later, software developer Ryan Pearce has taken inspiration from those early days to build Searcha Page, a homegrown search engine — along with a privacy-focused variant called Seek Ninja — hosted not in a Silicon Valley data center, but in his laundry room.

Google’s modest beginnings

Google’s origins are well documented. Backrub, its first iteration, ran on just 40 gigabytes of storage. The casing was made of Duplo blocks, a playful solution that symbolized both resourcefulness and constraint. As the project gained momentum, donations from IBM and Intel allowed founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin to move their fledgling system into a small server rack.

From there, growth became exponential. By 2025, Google’s operations spanned distributed networks of global data centers, far beyond the humble Duplo case. Its index ballooned from 24 million pages in 1998 to 400 billion by 2020, a number revealed during the 2023 U.S. v. Google antitrust trial.

A laundry room search engine

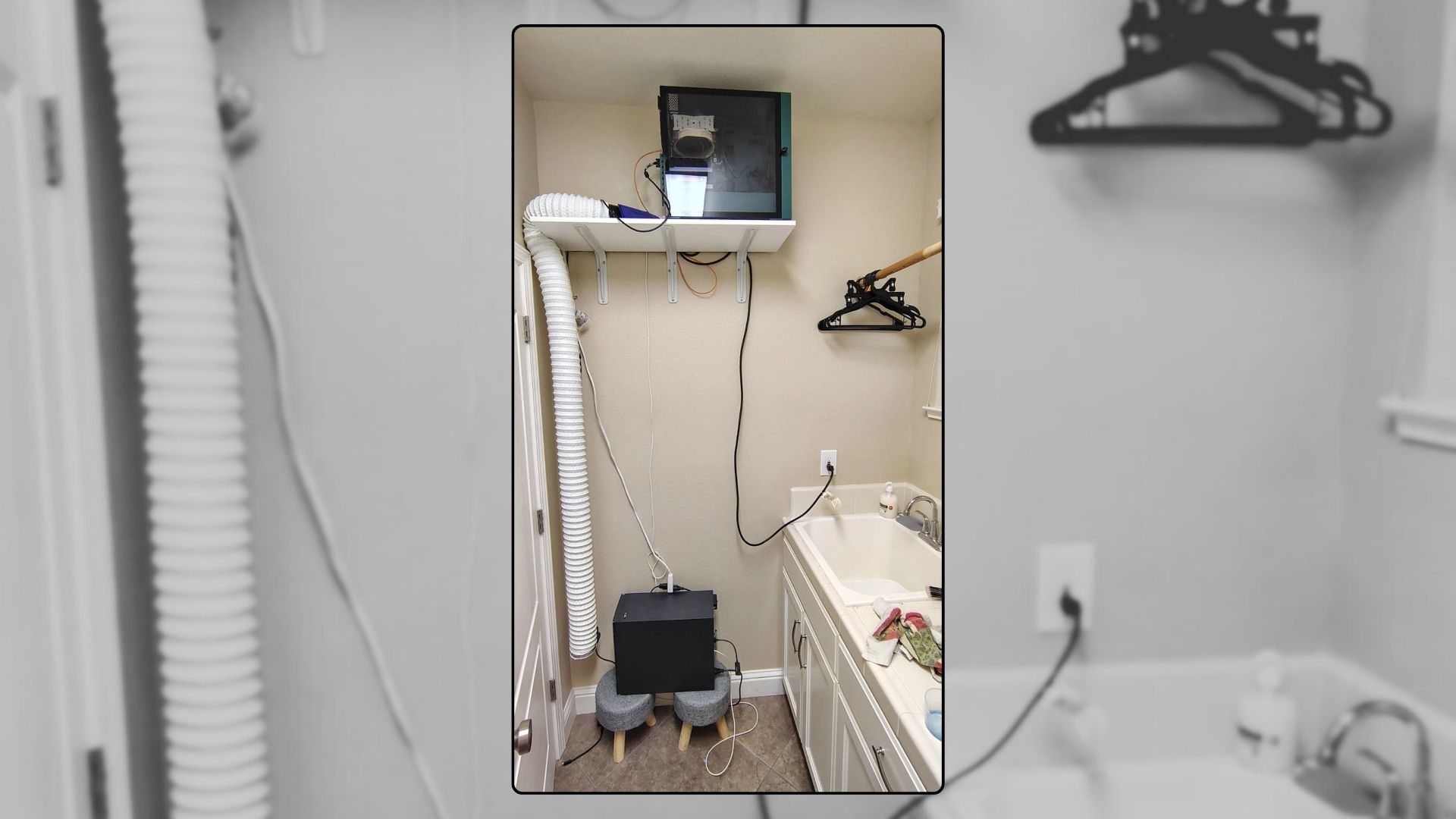

Pearce’s setup offers a striking contrast. Searcha Page and Seek Ninja run from his utility room at home, a decision shaped by necessity. Initially placed in his bedroom, the server produced too much heat and noise. With input from his wife, Pearce relocated it to the laundry room, drilling new network connections and adjusting ventilation to keep the system operational.

Despite these challenges, his search engine currently indexes 2 billion pages — with a goal of 4 billion within six months. “Right now, in the laundry room, I have more storage than Google in 2000 had,” Pearce noted, highlighting how modern hardware has compressed decades of technological progress into affordable, consumer-accessible systems.

Building on limited resources

Pearce built his project through self-hosting and hardware arbitrage. By buying second-hand servers, he acquired high-end components for a fraction of their original cost. His current setup includes a 32-core AMD EPYC 7532, once priced at over $3,000 but purchased for under $200 on eBay. The total system cost around $5,000, with $3,000 dedicated to storage and half a terabyte of RAM.

Running this operation at home presents obvious trade-offs. Heat management, noise, and power draw all need constant balancing. But the savings compared to cloud hosting are considerable. Pearce’s approach is the opposite of hobbyists like Wilson Lin, who rely on multiple cloud services to reduce overhead.

Search powered by AI

Searcha Page blends traditional search techniques with artificial intelligence. Large language models (LLMs) expand keywords and improve query understanding, enhancing relevance. “What I’m doing is actually very traditional search. It’s what Google did probably 20 years ago, except the only tweak is that I do use AI to do keyword expansion and assist with context understanding,” Pearce explained.

The reliance on AI mirrors industry trends. By 2019, Microsoft revealed that 90% of Bing’s search results were machine learning–driven. Google’s RankBrain, launched nearly a decade ago, embedded AI deeper into ranking systems. Pearce’s lightweight use of LLMs — accessed through services like SambaNova’s Llama 3 — illustrates how independent developers can leverage the same tools that power corporate giants.

Iteration and code at scale

Pearce estimates his project contains 150,000 lines of active code, but the iterative process has cycled through nearly 500,000 lines. His development method starts with LLM-powered prototypes, later optimized into traditional code for efficiency.

This hybrid strategy has allowed him to test features quickly, including LLM-generated page summaries, a feature Google and Bing now deliver at vast scale. While vector databases initially produced “very artistic” results, Pearce continues refining his infrastructure to balance accuracy, speed, and cost.

Privacy and niche ambitions

Seek Ninja, the privacy-focused variant of Pearce’s engine, is part of his vision to offer alternatives to ad-driven, data-heavy search ecosystems. Initially, he hoped to prioritize smaller websites over dominant corporations — an approach similar to Marginalia, a noncommercial search engine. While this remains a future ambition, it demonstrates how alternative search tools can diversify the web experience.

International interest is already emerging. Pearce said he was approached by someone in China seeking an uncensored search backend for an LLM agent, signaling global demand for independent search tools.

Challenges and the road ahead

Operating in English only, Searcha Page remains far smaller than Google’s infrastructure — “a drop in the bucket,” as Pearce admits. Expanding into other languages would require substantial new datasets and algorithmic adjustments. For now, his 2 billion–page database is proof of what can be accomplished outside corporate labs.

Long term, Pearce plans to move his system out of the laundry room and into a colocation facility, retaining control while scaling beyond home limits. He has also begun testing affiliate-style ads to offset costs, aiming for a less intrusive model than traditional web advertising.

“My plan is if I get past a certain traffic amount, I am going to get hosted. It’s not going to be in that laundry room forever,” Pearce said.

An inspiration for all

From Google’s Duplo case to Pearce’s laundry room, the history of search highlights a recurring theme: ingenuity often begins with modest infrastructure.

Advances in AI, storage, and affordable hardware now make it possible for independent developers to compete, at least in spirit, with the most resource-intensive tech companies.

Searcha Page and Seek Ninja may never rival Google’s 400-billion-page index, but their existence is a reminder that search innovation does not belong solely to Silicon Valley.