This post appeared originally in the dataArtisans blog

Six Common Streaming Misconceptions

Needless to say, we here at data Artisans spend a lot of time thinking about stream processing. Even cooler: we spend a lot of time helping others think about stream processing and how to apply streaming to data problems in their organizations.

A good first step in this process is understanding misconceptions about the modern stream processing space (and as a rapidly-changing space high in its hype cycle, there are many misconceptions worth talking about).

We’ve selected six of them to walk through in this post, and since Apache Flink® is the open-source stream processing framework that we’re most familiar with, we’ll provide examples in the context of Flink.

Myth 1: There’s no streaming without batch (the Lambda Architecture)

Myth 2: Latency and Throughput: Choose One

Myth 3: Micro-batching means better throughput

Myth 4: Exactly once? Completely impossible.

Myth 5: Streaming only applies to “real-time”

Myth 6: So what? Streaming is too hard anyway.

Myth 1: There’s no streaming without batch (the Lambda Architecture)

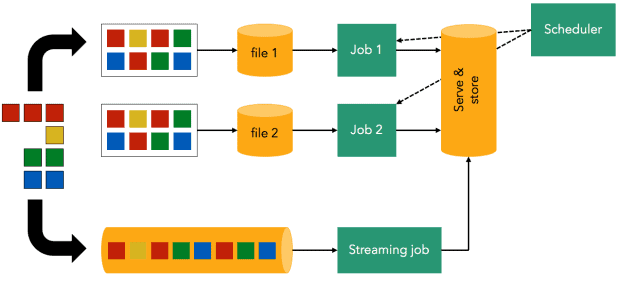

The “Lambda Architecture” was a useful and popular design pattern in the early days of Apache Storm and stream processing in general. The architecture consists of a “fast stream layer” that is augmented by a “batch layer”.

The reason for these two separate layers was that stream processing in the Lambda Architecture could only compute approximate results (for example, if there was a failure, the results could not be trusted) and could handle only a relatively low volume of events.

While these limitations existed in early versions of Apache Storm, they are no longer relevant in modern open-source stream processing–many stream processing frameworks are now fault tolerant, producing accurate results under failures, and are still capable of high-throughput computing. And so there’s no need to maintain a multi-layer architecture to for the sake of both “fast” and “accurate” results. A modern stream processor (such as Flink) gets you both.

The good news: we don’t hear much about the Lambda Architecture any more–a sign that the stream processing space is maturing.

Myth 2: Latency and Throughput: Choose One

Early open-source stream processors were classified as either “high-throughput” or “low-latency”, and so the assumption has stuck that “a lot of data, quickly” isn’t an option in open-source streaming.

But Flink (and potentially others, too) offers both high-throughput and low latency; here’s one example of results from a benchmark to put some hard numbers on the assertion.

Let us examine this from a fundamental viewpoint, in particular at the hardware level, and let us consider a stream processing pipeline that is network-bottlenecked (which is the case, at least, for many pipelines we see that are using Flink). At the hardware level, there is no reason for such a tradeoff to exist. The network’s capacity is ultimately what dictates both the maximum attainable throughput and the lowest attainable latency.

A well-engineered software system will achieve the physical limits allowed by the network and not introduce bottlenecks itself. While there is always room to optimize the performance of Flink and bring it closer to what is attainable by hardware, at this point, Flink has been shown to handle 10s of millions of events per second in a 10-node cluster, scale to 1000s of nodes, and at the same time achieve latency in the tens of milliseconds. In our experience, this level of performance is more than sufficient for most practical deployments.

Myth 3: Micro-batching means better throughput

There’s another side to the performance discussion, and first, we should clarify two often-confused terms:

Micro-batching

An execution and programming model for data processing that is built on top of a traditional batch model. The “technique allows a process or task to treat a stream as a sequence of small batches or chunks of data.”

Buffering

An optimization technique for accessing networks, disks, caches, etc. Wikipedia provides a perfectly fine definition: “A region of a physical memory storage used to temporarily store data while it is being moved from one place to another.”

The myth, then, is that data processing frameworks that use micro-batching are capable of higher throughput than streaming frameworks that process event-at-a-time because micro-batching sends data across the network more efficiently.

What this myth overlooks, though, is that while a streaming framework will not rely on any sort of batching at the processing or programming model level, it will almost definitely buffer at the physical level.

And Flink absolutely buffers data, meaning that it sends collections of processed records over the network rather than sending one single record at a time. To not buffer data wouldn’t make sense from a performance standpoint–there’s no benefit to sending records over the network one-at-a-time. So we’ll concede that there’s no such thing as record-at-a-time at a physical level.

But buffering serves only as a performance optimization. And therefore, buffering:

- Should be opaque to the user

- Should not dictate system behavior in any other way

- Should not impose artificial boundaries

- Should not limit what you can do with the system

So while a user of Flink APIs can develop as though the program is processing each record independently, Flink uses buffering to achieve its performance under the hood.

In fact, micro-batching can introduce considerable overhead in the form of scheduling tasks–and when tuning for lower latency (with a higher volume of smaller batches), this overhead only increases! A stream processor can deliver all of the advantages of buffering with none of the task-scheduling overhead.

Myth 4: Exactly once? Completely impossible.

There are a few sub-variations of this myth, including:

- Exactly once is impossible in nature

- Exactly once is impossible end-to-end

- Exactly once is never a real-world requirement anyway

- Exactly once requires a significant performance trade-off

Let’s take a step back: we’re not thrilled to be getting into ‘exactly once’ in this post. Historically, ‘exactly once’ has referred only to ‘exactly once delivery’, but the phrase is now embedded in the stream processing lexicon and is used fairly loosely, making the two words more confusing and less descriptive than they used to be. The related concepts are still important, though, and so we won’t skip over it altogether.

To try to be as precise as possible, we’ll break out ‘exactly once state’ and ‘exactly once delivery’ as separate ideas. The confusion between state and delivery stems from prior uses of these terms. For example, while Apache Storm used the term ‘at least once’ implying delivery (Storm did not offer support for state), Apache Samza used the term ‘at least once’ implying application state guarantees.

Exactly-once state means that the state of the application after a failure will be as if no failure had occurred. For example, if we are maintaining a counter application and experience a failure, we will neither undercount nor overcount within the application. The reason for using the term ‘exactly-once’ in this context is that the application state is always as if each message was processed exactly once.

Exactly-once delivery means that after a failure, the recipient (some system outside of the application) will receive processed events as if there was no failure.

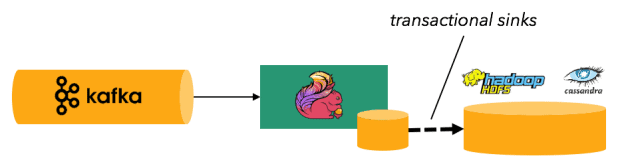

While the latter (delivery) is impossible for a stream processing framework to guarantee in every single scenario, the former (state) is both possible, and in the case of Flink, possible without a meaningful performance hit. And Flink is also capable of exactly once delivery to selected data sinks that cooperate with Flink’s checkpointing.

Flink’s checkpoints are periodic, asynchronous, and consistent snapshots of application state. This is how Flink is able to provide the aforementioned exactly-once state guarantees under failure: Flink periodically records (snapshots) the position it is reading in the input stream as well as the corresponding state of every operator. If there is a failure, Flink rolls back both the input stream and the operator state to a prior, consistent, global state and restarts the computation from there. Hence, even if records are replayed, the resulting state is as if the records were processed exactly once.

And end-to-end exactly once processing? It’s possible to build applications so that checkpoints double as a transaction coordination mechanism–in other words, source and sink operators can also take part in checkpoints. The result is exactly-once processing inside the framework and exactly-once or “effectively-once” processing end-to-end. For example, when using Flink with Kafka as source and a rolling file sink (e.g. HDFS), one can achieve end-to-end exactly once from Kafka to HDFS. Similarly, when using Kafka as the Flink source and Cassandra as the sink, one can get end-to-end exactly once when updates to Cassandra are idempotent.

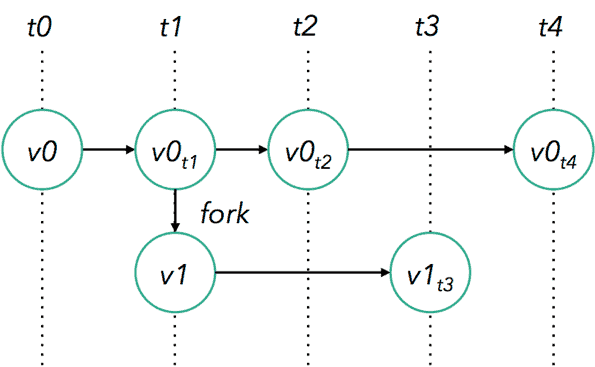

It’s worth mentioning that checkpoints can also triple as a state versioning mechanism via Flink’s savepoints. With savepoints, it’s possible to ‘move around in time’ while maintaining state consistency. This enables easy code updates, maintenance, migration, debugging, and even A/B testing or ‘what-if?’ simulations.

Myth 5: Streaming only applies to “real-time”

Variations of this myth include:

- “I don’t have low-latency applications, and therefore I don’t need a stream processor.”

- “Stream processing is only relevant for transient data before we move it to storage.”

- “We need a batch processor to do heavy, offline computations.”

Now it’s time to think about types of datasets vs. types of execution models.

First, two types of datasets

- Unbounded: Data that’s produced continuously without a defined end point

- Bounded: Data that’s finite and should be considered complete

Many real-world datasets are, in fact, unbounded datasets. This is true whether the data is stored in a sequence of files or directories on HDFS or in a log-based system like Apache Kafka. Examples include but are not limited to:

- End users interacting with mobile or web applications

- Physical sensors providing measurements

- Financial markets

- Machine log data

In fact, it is quite hard to find a real-world example of a dataset in a modern business that is bounded, except perhaps the location of all of a company’s buildings and facilities (but this, too, evolves as the business grows).

Second, two types of execution models

- Streaming: Processing that executes continuously as long as data is being produced

- Batch: Processing that is executed and runs to completeness in a finite amount of time, releasing computing resources when finished

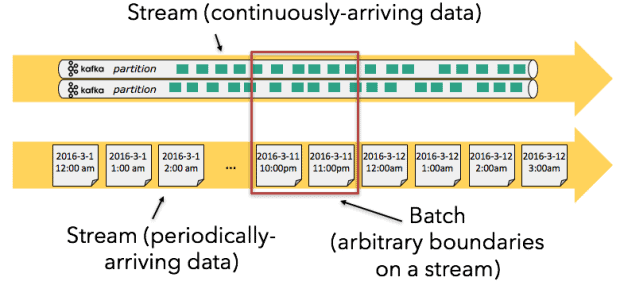

Let’s go one step further and identify two categories of unbounded datasets: streams with continuously-arriving data and streams with periodically-arriving data.

It’s possible, though not necessarily optimal, to process either type of dataset using either type of execution model–for instance, batch execution has long been applied to unbounded datasets, especially unbounded datasets with periodically-arriving data. In reality, most “batch” jobs are executed according to some schedule, analyzing unbounded datasets by only touching a small part of the stream at a time. This often means the unbounded nature of the stream becomes someone else’s problem (usually whoever’s working on the ingestion pipeline).

Batch processing gives the impression that it is stateless, in that the output only depends on the input. In reality, batch jobs keep state internally (e.g. a reducer always keeps state), but this state is confined within the boundaries of the batch, and there is no way to correlate events across batches.

And ‘state confined within the boundaries of the batch’ matters as soon as a user tries to implement something as simple as windowing with an ‘event time’ time characteristic–a very common approach when working with unbounded data.

It’s inevitable that a batch processor working on an unbounded dataset will have to deal with late-arriving events (because of an upstream delay, etc.), and when events arrive late, the data inside of a given batch is at risk of being incomplete–remember, we assume that we’re generating our windows based on event time because this is the time characteristic that provides the most accurate model of reality. In batch execution, late-arriving data presents a problem even with simple fixed windows (e.g. tumbling or sliding windows) and becomes more difficult to deal with when using session windows.

Because if all of the data required to complete a computation isn’t in the same batch, then it’s not possible to arrive at correct results on an unbounded dataset when using batch execution–at least, not without a lot of additional overhead to deal with late data and state between batches (delaying processing until you’re sure all data has arrived, re-processing a batch).

Flink has a built-in mechanism for dealing with late elements–late data is assumed to be a normal occurrence when working with unbounded data in the real world, and so a well-designed stream processor will offer simple tooling to handle late data.

Stateful stream processing is a more naturally-fitting model for unbounded datasets regardless of whether the dataset is ‘continuously-arriving’ or ‘periodically-arriving’. The potential to compute in real-time is just icing on the cake when working with a stream processor.

For more on the topic, these issues are well-documented in Tyler Akidau’s Streaming 101.

Myth 6: So what? Streaming is too hard anyway.

OK, we’re at the last stage. That stage where you think, “This sounds great on paper, but I’m still not gonna adopt a streaming technology because…”:

- Streaming frameworks are hard to learn.

- Streaming is hard to reason about: Windows? Event time? Triggers? Yikes!

- Streaming needs to be coupled with batch, and I know batch already. So what’s the point?

We’re never going to advocate that you should adopt streaming just because we happen to think streaming is cool. Rather, we believe that the decision to use a streaming execution model should ultimately depend on the nature of your data and the nature of your code.

Let us ask again, “What type of dataset am I working with?”

- Unbounded (e.g. user activity, logs, sensor data)

- Bounded (e.g. ______?)

And then ask a different question: “What changes more frequently?”

- My code changes more frequently than my data.

- My data changes more frequently than my code.

If your data changes more frequently than your code–for example, a ‘standing’ query that remains more or less static and is updated occasionally for bug fixing, applied to an ever-changing set of data–we would argue that you have a streaming problem.

So before you write streaming off as ‘too hard’, consider that there’s a good chance you’re already solving a streaming problem in some capacity! You might be solving your streaming problem with hourly batch jobs, and someone else on your team might own the creation and management of the hourly batches (in which case you’re probably living with inaccurate results without realizing it due to batch’s issues with time handling and state that we mentioned above).

The Flink community has long worked to deliver higher-level APIs that abstract away many of the intricacies of time and state. For example, dealing with event time in Flink is as simple as defining a window of time and a function that extracts timestamps and watermarks (which only needs to be done once per stream). Dealing with state is as easy as defining variables in a Java program and registering them with Flink. And efforts such as Flink’s StreamSQL will allow you to run SQL queries on your never-ending streams.

To finish the thought exercise: what if your code changes more quickly than your data? In that case, we contend that you have an exploration problem. And using notebooks or other, similar tools for iteration might be a perfect fit for solving an exploration problem.

As soon as your code stabilizes, though, you’ll end up with a streaming problem. And we recommend that you start thinking about a long-term solution in a streaming context from the very beginning.

Stream processing’s next act

As the stream processing space matures and these myths become less and less prevalent in everyday discussion (such as how we almost never hear a reference to the Lambda architecture any more), we also see that streaming is evolving beyond its initial place in analytics applications.

As we discussed, most real-world data is produced continuously and arrives continuously. Traditionally, this continuous data flow had to be interrupted, and data had to be either gathered in a central location or cut in batches in order for applications to interact with it.

With the streaming paradigm and patterns such as CQRS becoming more popular, applications can be developed directly on continuously-flowing data, enabling benefits such as localized and correct state, better isolation of applications and teams, and better handling of time series data.

We believe that Flink, as it further evolves and is adopted by more and more enterprises, has the potential not only to streamline analytics pipelines, but also to introduce a new, far-reaching, and more powerful computational model.

Like this article? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to never miss out!